-

What is security?

I'm sure my loyal readers will think that this article is about computer security as I write a lot about computers and technology, but this article is about physical home security.

With a complete house remodel planned, I've been thinking a lot about securing our house. I've been reading everything I can, watching videos, and even testing security first hand. There are articles and videos about locks, bumping, picking, and using tools to break locks. There is also information about reinforcing door jams and security systems. With all this information, I really have to ask "what is the purpose of securing a house?". That question may sound simplistic, but it is relevant. Unless we build our house like Fort Knox with armed guards and basically no windows, there will always be ways to get in.

Let's start with locks. There are locks in every shape, size, and strength. Does a lock really matter? Well, I've seen videos of people kicking in doors and, of course, we've all seen TV shows with police using a battering ram to go right through the lock. So, someone determined to get in through the front door will definitely do it. A reasonable quality lock is a decent deterrent. Next let's look at a security screen door. What is the purpose of it? I managed to break the lock on our security screen door (not on purpose) and with my father's help, we broke the door in about a minute using a tire iron. So, the security screen door isn't going to keep someone out, but will keep a solicitor from entering the house while we're getting a breeze through it.

If we move on to securing the door jam, it seems like a reasonable thing to do as I've seen videos of the door being kicked in and it is something to consider; however, as I mentioned above, a determined person will get in. No matter what you do to the front door, there are easier ways to get into a house. Windows (unless they are bullet resistant or very reinforced), are pretty easy to break or cut, so there is another way to get in. Locks on windows aren't of much use.

Looking at security systems, they only work after the fact when someone has already entered or attempted to enter your house.

So, what is the answer to security? I think it is quite simple, you need to deter anyone from attempting to get into your house and make your house not look like an easy target. If you keep people away from touching your house, none of the physical security above actually matters. There are a number of ways to make your house look less attractive for a criminal, none of these is revolutionary and hasn't been said before:

- Use motion sensing lights. This is pretty obvious, but a lot of people don't have this and sometimes they are a nuisance, so they're turned off.

- Install cameras that are visible as well as post signs indicating that the property is being video taped. The recordings, themselves, may not actually help to catch an intruder, but the presence may get someone to think twice about approaching. Also, depending on the type of system, you could trigger alerts of someone approaching.

- Watch your routines. In our last house, we always parked our cars in the garage, so if someone looked at our house, he wouldn't know if we were home or not. In our rental, we can't get our cars in the garage, so the presence of our cars means we're home and the lack of one or both means we're not home. When I travel, I take a cab to the airport or get a ride to make it less obvious that I'm not home. In our new house, we're definitely going to get both cars in the garage.

- Don't broadcast your whereabouts on social networks. This is pretty obvious, but have you ever looked at the number of people that checkin somewhere and post on a social network?

- Lock your back gate.

- Don't give people a place to hide around your house; trim back bushes and trees directly adjacent to your house.

I'm going to use a combination of things to secure my house, but am under no illusion that my house will be completely secure, because that just isn't possible.

Am I an expert on this? No, I'm just a regular home owner that has done some thinking about this problem.

-

When letters to companies work

Sometime last year, my wife and I went to Road Runner Sports to get new shoes. They've always had a decent selection and with their VIP club, we can wear the shoes for awhile and return them if they don't work out. This is extremely important to me as I run a bit and if the shoes aren't comfortable, I need to find a replacement. When we went, they were advertising an extra 10% off (VIP members get 10% off already). After we left the store, I realized that their advertised 20% off (10% off for VIP + 10% off for the sale) was not actually 20%. They took the 10% off first and then from the new price, took another 10% off. So for a $100 purchase, 20% off makes the cost $80. However, they were charging $81 (10% off $100 = $90 and the 10% off that make $81). This is not a huge deal taken in isolation, but irked me enough that I sent a letter to the company CEO.

I got a call from the CEO and he refunded me a few bucks and said that he'd look into it. I figured he was just trying to placate me as they'd have to fix their computer systems to correctly apply the discount across the board. Today we were in the store to purchase new shoes and they were advertising 20% off (10% VIP + 10%) and I was expecting to put up a fight for the correct 20% off. I was pleasantly surprised to find that they took 20% off the original price with no funny business.

This was an excellent move by Road Runner Sports to correct something that most people would not have noticed. I'm not sure if originally they intended to incorrectly advertise the 20% off or it was just a mistake that no one caught. However, I am happy that they did the right thing.

Now I just hope my new shoes are comfortable as I don't want to have to find different ones!

-

Review: SecuritySpy

In our last house, I considered adding security cameras as my wife was a teacher in the area and some of the students knew where she lived. We all know that not every student is perfect and we wouldn't be surprised if a student toilet papered our house. This, luckily never happened. However, neighborhood kids did toilet paper our house once and someone (or a group of individuals) graffitied a number of houses including ours with anti-Semitic words and symbols. I never got around to installing cameras and it is probably best that I didn't as the technology has gotten so much better, that the quality of cameras and systems from just a few years ago doesn't compare with what we have today.

Some people may think I'm a bit paranoid, but I think that knowing who is around my property while it is being remodeling as well as down the line knowing if solicitors come to the door or a package gets dropped off is invaluable.

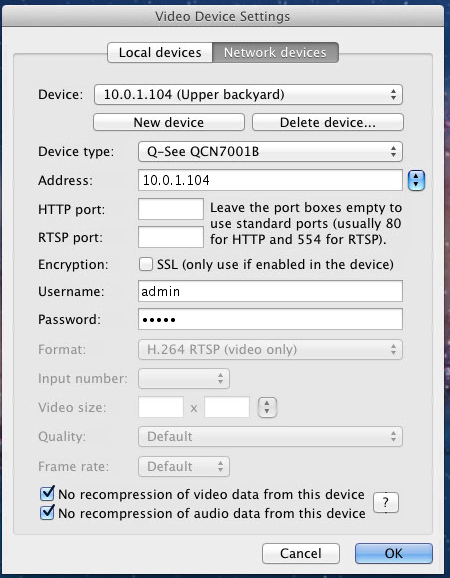

When I started investigating camera systems, the reviews on full featured systems were so mixed that I didn't know what to believe and what not to believe. The most common theme among reviews on systems was that the fans in the DVRs was noisy and that the boxes were power hogs. That quickly changed my thinking and I decided that since my Mac Mini that acts as my media center runs most of the time (6 am to 11 pm), I was probably better off having it run 24 hours a day and have it handle the recording. The latest Mac Minis use about 85 W and are super quiet. With that decision made, I had to go with networked, IP cameras. I'll cover the Q-See cameras I got in another review. So the last decision to be made was the software to handle the recordings. Unfortunately, there aren't many options for the Mac.

After playing with the 2 leading candidates, I decided that SecuritySpy was the only option. The other candidate crashed while I was testing it, which made it unreliable for a 24/7 system.

SecuritySpy grew out of a product called BTV which I had played with a number of years ago when I first started experimenting with video on the Mac at about the time I wrote a program called PhotoCapture, if I recall correctly. (As an interesting side note, PhotoCapture was effectively a security program for capturing still images, but was either triggered on a timer or when someone hit a web page.)

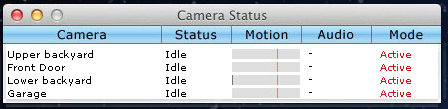

SecuritySpy has a few main functions that I have used; the first is time lapse recording that gives you a new recording every day for each camera. The second is to do something when it detects motion. For the first week that I used SecuritySpy, I had time lapse recording turned on and it recorded lots and lots of video. I had the cameras set to output H.264 video at 15 fps. For each camera, SecuritySpy was recording over 30 GB of data per data. With four cameras, this amounted to about 120 GB of video a day. SecuritySpy will remove old video or keep a certain amount of free space, so space was only a slight issue (my test Mac Mini is a Core 2 Duo 2.0 GHz machine with a 500 GB drive; when I eventually move, my main Mac Mini will take over the duties). The big question really is, what will I do with so much video?

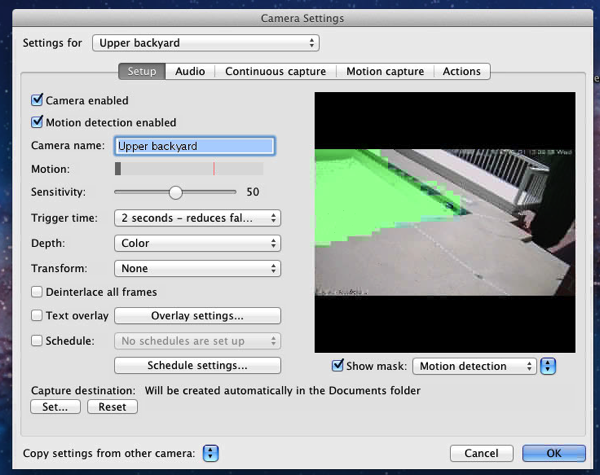

The second main feature of SecuritySpy is the motion detection triggers. I've set it up to record 15 seconds of video before and after an event as well as capture still images once a second during that time and email me the images. This feature is where the power of SecuritySpy lies. Quickly I realized that I had to mask off some areas of the image to ignore as the shimmering of the pool kept triggering the motion. I've been receiving images all week long of the mailman coming to the door, a contractor pulling into the driveway, as well as my smiling face when I've approached the front door! I still need to tweak my settings, but now I know who is approaching the house (I also have cameras in the back as well).

Configuration of SecuritySpy, however, is a bit cumbersome. In my case, my 4 cameras are identical with the exception of the IP address and I want the same motion capture settings. For the setup, I have to add each camera individually, select the camera from a list and set a few settings. After that setup is done, you have to navigate to each camera individually and set it up; there is an option to copy all the settings from another camera which helps, but there is likely an easier way to configure all cameras at once.

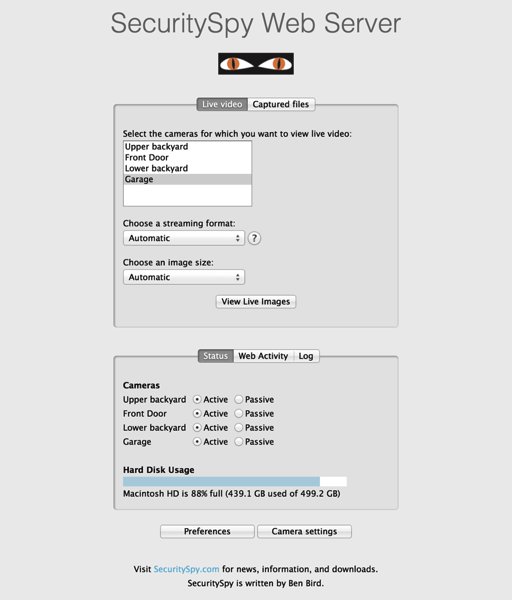

Another neat feature is that it has a built in web server so that you can view from anywhere. With a change to port forwarding on your router and the built in dynamic DNS for SecuritySpy, it is easy to access your machine remotely. However, if you want to use HTTPS to securely access it, the process is a bit cumbersome as it requires setting up the web server built into OS X (in Mountain Lion and maybe Lion, there is no longer a checkbox to turn on the web server in System Preferences), setting up a rewrite rule and installing a certificate. I would have preferred to have this built into SecuritySpy with the ability to either have it generate a self-signed certificate or allow the user to select his own (I use StartSSL for free certificates that work with a wide variety of operating systems; I'm not sure I'd use them for anything other than my personal use, however). The web interface for SecuritySpy feels quite dated and reminds me of the kinds of things I setup in 1994 when working with my PhotoCapture program. It definitely could use an overhaul, but it is quite functional.

Like the web interface, the entire user interface feels quite dated. The dialogs, windows, etc. look very Carbon like and show the roots of the program dating back almost 20 years. While I am definitely not a user interface designer, basic Cocoa apps look a lot fresher than SecuritySpy. I know it is quite hard to transition a UI and if you're a one man shop, you may not have the resources to revamp the UI.

On my Core 2 Duo Mac Mini, SecuritySpy has had no problems keeping up with 15 fps video on 4 cameras. It uses somewhere between 40 and 60% of the CPU (total between both cores) which is what I expected. When I switch it over to my quad core i7 Mac Mini, the Mini should have no problems acting as my regular DVR and security setup. This was on version 3.0.2; I am still testing the latest 3.0.4 version, but preliminary testing shows an issue indicating that there are network errors and the machine may not be able to keep up with the 15 fps.

Pros

- Works with a variety of cameras.

- Very robust.

- Motion capture works well.

- Full suite of actions on motion.

- Built in web server works well for remote access.

Cons

- User interface feels dated.

- Web interface feels dated.

- Configuration could be a little easier.

- HTTPS isn't built into the web server.

Summary

SecuritySpy is an excellent alternative to standalone surveillance systems. The website has estimates on hardware requirements and those should be looked at closely so that you're not disappointed with performance. The price for the 4 cameras is about $120 which I consider quite reasonable as I compared it to a standalone system (incremental cost since I already had a Mac Mini; some standalone systems cost maybe $100 more when bundled with 4 cameras). Setting up a video system is not for the faint of heart; adding a Mac Mini to the equation makes it even more complicated. However, I believe that SecuritySpy and using a Mac Mini was a wise choice for me. I did contact support about compatibility with a camera I tried out before the Q-See ones and got a very prompt response about it; so if you run into problems, help is out there.

-

Making our house a home

Over a year ago, my wife and I decided to sell our house and move closer to the water. We expected to be in a rental for maybe 6 months before finding a house. We were fully prepared to wait and wanted a fixer. Unfortunately, the real estate market here in San Diego started heating up again and finding a house was not an easy task. We had a few requirements for a house, but looking back, we were actually flexible on some of those requirements.

11 months and offers on 6 houses later, we finally found the house that we'll eventually call home. I say eventually because we have a very large remodeling project. While a lot of the remodeling is interior and cosmetic, we are filling in a pool (yes, people think we're crazy, but having had a pool for 8 years where it was warmer than where are are now and not using it much, we've decided that it isn't worth keeping), removing a fireplace (switching to a gas appliance fireplace), rearranging some rooms a little, adding some closets, and fixing up the kitchen. This project is going to take awhile and while we're very anxious to get moved in, I'm sure the time will start flying by as the process gets underway. Of course we want it done right the first time, so we're not going to rush it.

I'm not quite sure how most people go about remodeling a house as there seem to be lots of hurdles and pitfalls. Luckily, I have a construction expert (my father), who has offered to oversee the work and guide me.

Let the fun begin!